. If a healthcare worker contracts COVID-19, not only does their illness have personal consequences, which may be severe, it also increases the burden on the healthcare system, and reduces the capacity of the system to deal with future patients.

During SARS, healthcare workers made up approximately 20% of worldwide infections (Chan-Yeung, 2004). Media reports suggest that over 60 Italian doctors have died from COVID-19 (CNN, 2020).

The capacity of healthcare systems across Australia and New Zealand are expected to be challenged by the COVID-19 pandemic. If a healthcare worker contracts COVID-19, not only does their illness have personal consequences, which may be severe, it also increases the burden on the healthcare system, and reduces the capacity of the system to deal with future patients.

We recommend:

- During the period in which there is a COVID-19 epidemic in the country and high rates of community transmission, unless there is clear evidence to the contrary, any collapsed / unresponsive patient should be assumed to be high-risk for COVID-19.

- Health care workers should only perform resuscitative interventions when they are protected by appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE).

- Health care workers must not perform resuscitative interventions if they are not adequately protected by appropriate PPE.

Therefore, modifications to the traditional approach to cardiac arrest are needed.

We align with published guidelines and statements from:

- Australian Resuscitation Council. ARC Statements on COVID-19. [Link]

- New Zealand Resuscitation Council. Statements on COVID-19. [Link]

- Resuscitation Council UK. Statements and resources on COVID-19 (Coronavirus), CPR and Resuscitation. [Link]

- American Heart Association. Coronavirus (COVID-19) resources for CPR training & resuscitation. [Link]

- International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR). Consensus on Science with Treatment Recommendations (CoSTR): COVID-19 infection risk to rescuers from patients in cardiac arrest. [Link]

As the COVID-19 pandemic has progressed, there is some emerging evidence to guide this document. However, with an overall aim to ensure a safe working environment for healthcare workers, we have been deliberately conservative with many recommendations.

-

Is resuscitation appropriate?

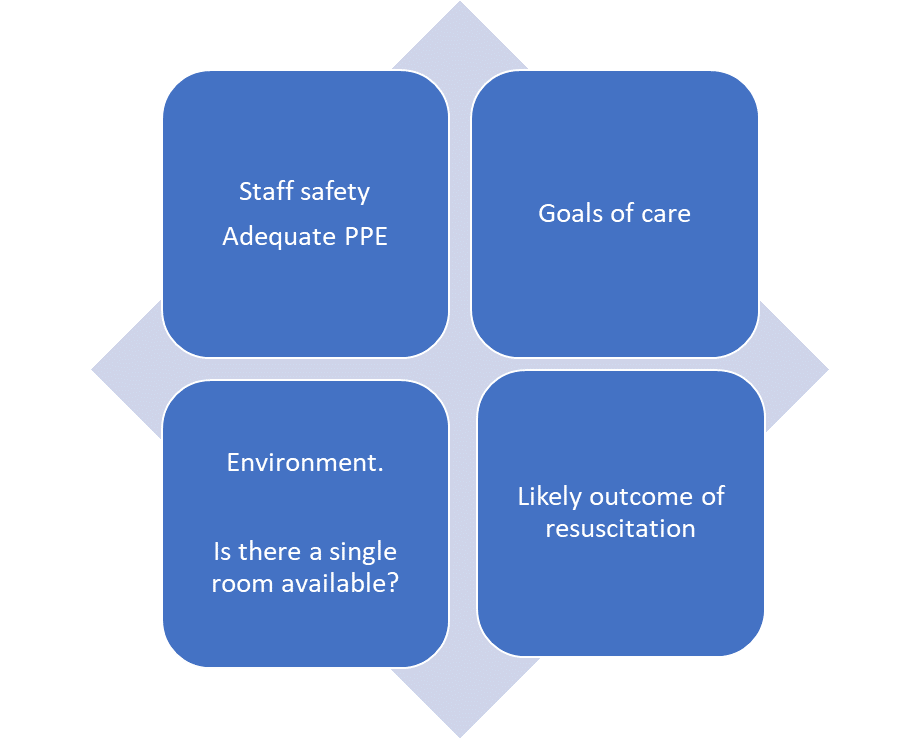

Before resuscitation commences, there are a number of factors which must be considered (Fritz and Perkins, 2020) (see Figure 8). These include:

- Are there any documented goals of care / advance care directives?

- What is the community prevalence of COVID-19?

- Are staff protected by appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE)?

- Is there an appropriate resuscitation setting (single or negative pressure room) available that limits risk to others?

- What is the chance of successful resuscitation with good neurological outcome?

- What is the risk to other patients in offering resuscitation?

Resuscitation should not proceed unless all staff are protected by adequate PPE.

It may become necessary in some jurisdictions for treating clinicians to exercise some resource-based decision-making discretion on the individual patient.Should this become necessary it must be discussed at jurisdictional level including with medical regulators to ensure that decisions are not made at the whim of an individual clinician, and that ethical principles still apply.

Figure 8. Factors to consider before resuscitation commences.

-

Summary of minimum personal protective equipment (PPE) for various resuscitation procedures

|

|

Surgical mask, eye protection and gloves

|

Droplet PPE:

- Surgical mask

- Eye protection

- Gloves

- Gown / apron

|

Airborne PPE

- N95/P2 mask

- Eye protection

- Gloves

- Gown / apron

- Visor, hat and neck protection as per local guidelines

|

|

First responder – recognise cardiac arrest and send for help

|

✔

Low-risk for COVID-19

or

unable to assess risk

|

✔

High-risk for COVID-19

|

|

|

Oxygen mask

(up to 10L/min) on patient. Consider covering with towel / cloth / clear plastic sheet / surgical mask

|

✔

Low-risk for COVID-19

or

unable to assess risk

|

✔

High-risk for COVID-19

|

✔

|

|

Initial (first-responder) compression-only CPR while awaiting staff in full airborne PPE

|

✔

Low-risk for COVID-19 or unable to assess risk

|

✔

High-risk for COVID-19

|

✔

|

|

Defibrillation

(with patient’s face covered)

|

✔

Low-risk for COVID-19

or

unable to assess risk

|

✔

High-risk for COVID-19

|

✔

|

|

Ongoing chest compressions during CPR

|

✔

Low-risk for COVID-19

|

|

✔

High-risk for COVID-19 or unable to assess risk

|

|

Basic airway manoeuvres (chin lift / head-tilt / jaw thrust)

|

✔

Low-risk for COVID-19

or

unable to assess risk

|

✔

High-risk for COVID-19

|

|

|

Oropharyngeal / nasopharyngeal airway

|

✔

Low-risk for COVID-19

|

|

✔

High-risk for COVID-19 or unable to assess risk

|

|

Intubation

|

✔

Low-risk for COVID-19

|

|

✔

High-risk for COVID-19 or unable to assess risk

|

|

Bag-mask ventilation

|

✔

Low-risk for COVID-19 |

|

✔

High-risk for COVID-19 or unable to assess risk |

|

Supraglottic airway

|

✔

Low-risk for COVID-19

|

|

✔

High-risk for COVID-19 or unable to assess risk

|

-

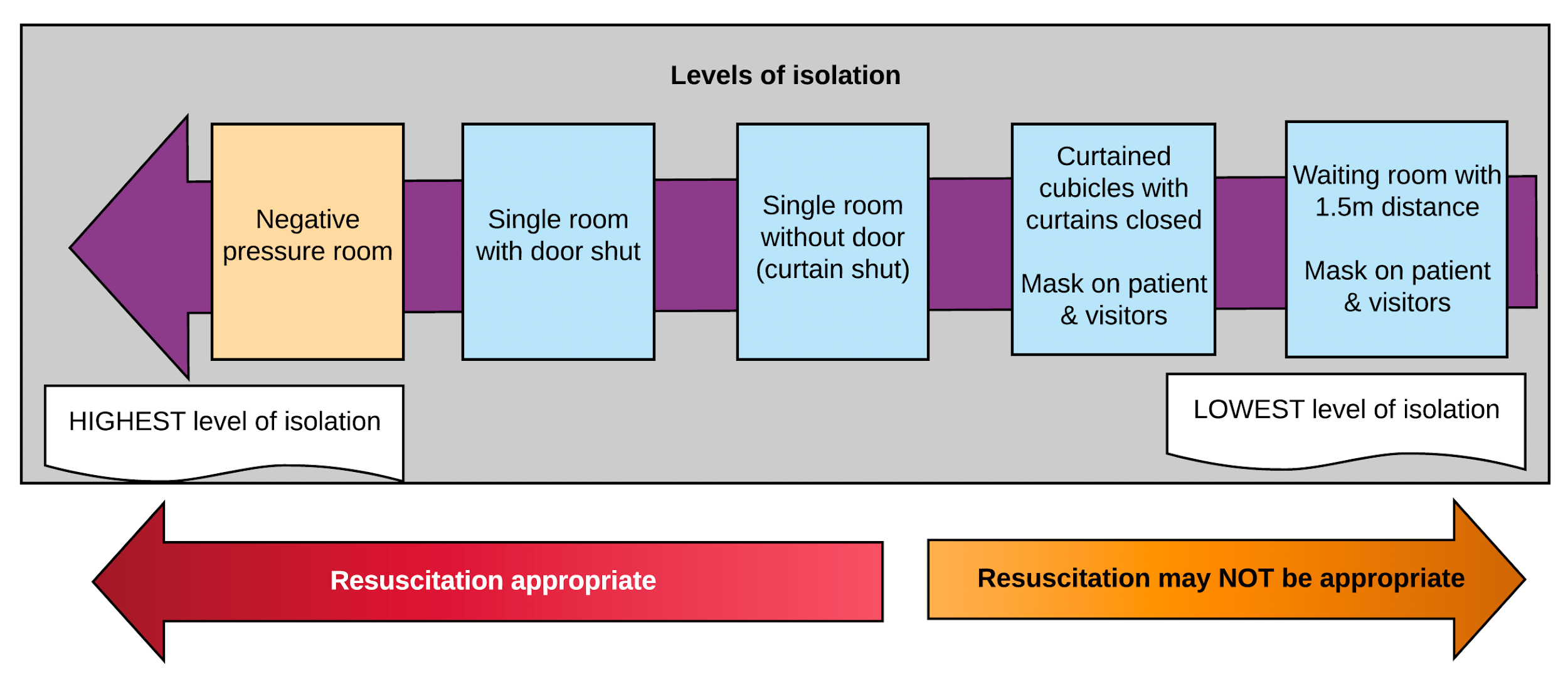

Optimal setting for resuscitation

We recommend:

- A single negative pressure room is the safest location for resuscitation procedures, and where possible patients should be moved to one as soon as practicable.

- Initial resuscitation should not be withheld if a single room is immediately unavailable.

- If a single room (negative pressure room, single room with a door, or single room with a curtain) is not available anywhere in the department, then the most senior clinician should consider whether it is appropriate to continue resuscitation. In particular, they should consider whether the potential risk of COVID-19 transmission to healthcare workers and other patients outweighs the possible benefit to the individual patient.In a setting where patients who are positive for COVID-19 are cohorted in an open ward, and all staff are wearing appropriate PPE, this consideration is less relevant.

Figure 9. Hierarchy of isolated treatment spaces.

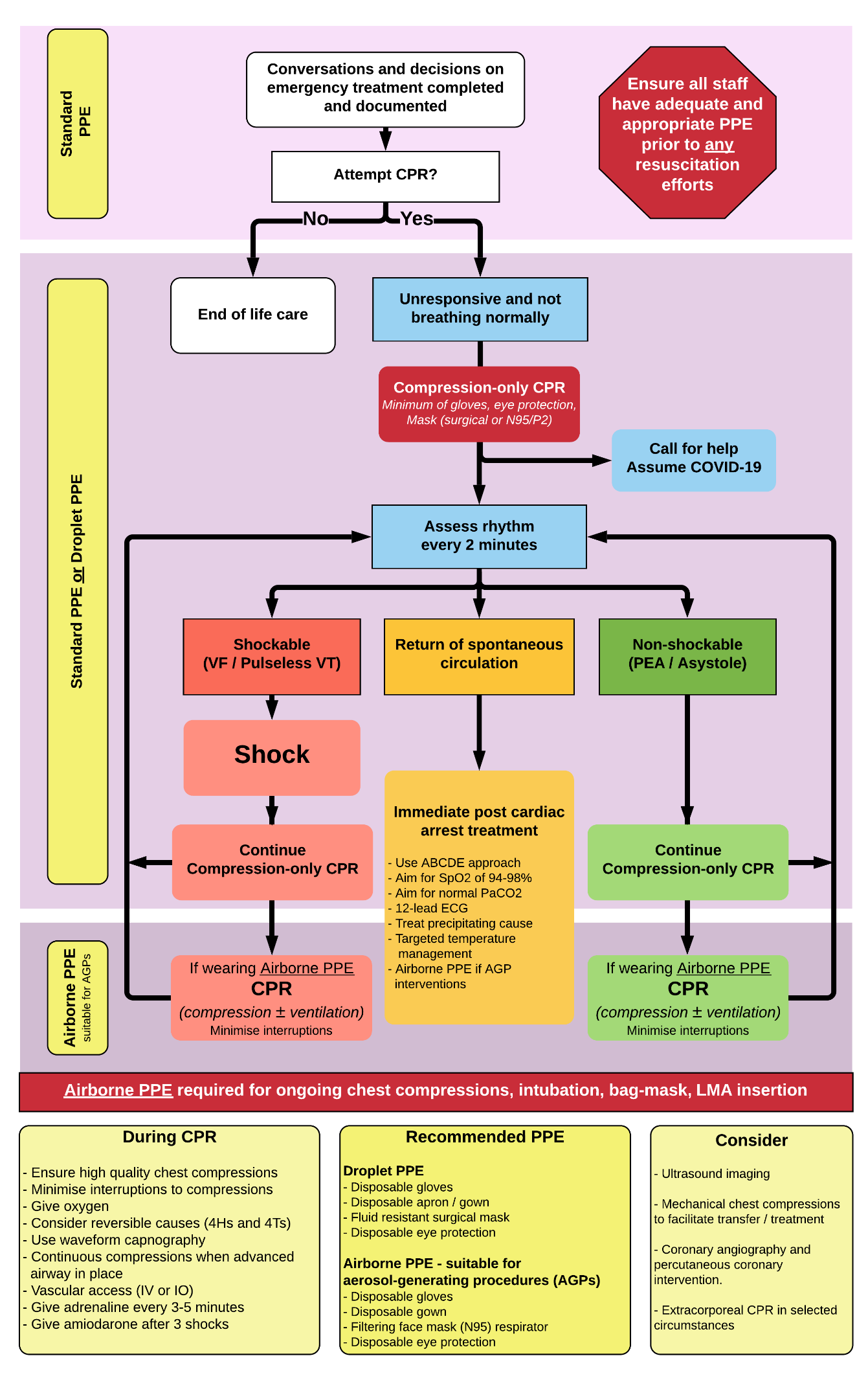

A suggested resuscitation algorithm is shown in Figure 10 below:

Figure 10. Suggested resuscitation algorithm.

Adapted from NZRC (with permission).

-

Staff safety and prevention of occupational exposure to COVID-19

We recommend:

- As community spread increases, all critically ill patients should be assumed to be infected with COVID-19.

- Goals of care and any limitations on resuscitation should be clarified early for all patients admitted to hospital.

- Maintenance of current systems to recognise clinical deterioration and prevent cardiorespiratory arrest due to progression of severe illness.

- Maintenance of access to palliative care protocols to ensure appropriate care for dying patients.

- All staff attending a collapsed patient should be wearing appropriate PPE. The level of PPE dictates which interventions may be safely provided by healthcare workers.

- A staff member should be specifically assigned to ensure safe PPE use. Specific attention should be paid to mask fit for staff members wearing airborne PPE, and to supervise any donning / doffing.

- Senior expertise is used to minimise the number of people involved in a resuscitation.

-

Modifications to cardiac arrest management in the COVID-19 era

We recommend:

Modifications to existing advanced life support protocols should be made in the following ways:

Danger

- Ideally, all resuscitation should be performed by healthcare workers in PPE suitable for aerosol generating procedures. However, it is recognised that this may not be the case for first responders.

- First responders should be wearing at least a surgical mask, eye protection and gloves.

- The patient’s face should be covered with a mask, towel or sheet to reduce the risk of aerosols during resuscitation. Supplemental oxygen can be provided prior to this, as long as administering oxygen does not delay other resuscitative interventions.

- A staff member wearing a minimum of gloves, eye protection, and surgical face mask should immediately place defibrillation pads on the chest, check the cardiac rhythm and defibrillate the patient if VF/pVT.

- Compression-only CPR (with the face covered) should be instituted rapidly by the first available staff member wearing a minimum of gloves, eye protection and a surgical mask (or N95 mask or P2 respirator if available).

- Ongoing resuscitation should be carried out by staff in full airborne PPE (gloves, eye protection, gown and N95 mask or P2 respirator) who should take over resuscitation as soon as possible. Any rescuers not wearing full airborne PPE should leave the area, remove their PPE and perform careful hand hygiene.

- Resuscitation should occur in the highest level of isolation available.

Response

- If the patient is unresponsive and not breathing normally, then resuscitation may be necessary. Call for help.

Airway and Breathing

- Do NOT provide positive pressure ventilation until in an appropriate room and wearing airborne PPE.

- Place a standard oxygen mask (e.g. Hudson mask) on the patient, and open their airway with a head tilt / chin lift.

- Provide oxygen at a flow rate of 10 L/minute.

- Listening or feeling for breathing should not occur. Instead, place a hand on patient’s chest to feel for chest rise and fall while assessing for normal breathing.

- Do not attempt to clear the airway using any methods other than head tilt or chin lift.

- Suctioning of the airway should not occur through an open suction device (i.e. Yankauer sucker) until in an appropriate room with airborne PPE.

- An appropriate viral filter must be connected to any oxygen delivery device, as close to the patient as possible. Take care to ensure that all connections are secure.

- Bag-mask ventilation should be minimised. If required, use two hands to hold the mask. Compressions should be paused, and the bag should be squeezed by a second rescuer at a compression:ventilation ratio of 30:2.

- Pause compressions before inserting a supraglottic airway or attempting to intubate.

- If additional oxygen delivery is required, a well-fitted supraglottic airway device (e.g. an i-gel) should be inserted, and connected to a Mapleson circuit (preferred) via an appropriate filter, or a standard self-inflating bag.

- If using a Mapleson circuit, connect the circuit to oxygen, but do not squeeze the bag. This will allow flow of oxygen without administration of positive pressure ventilation.

- If using a standard self-inflating bag, monitor the movement of the reservoir bag. If oxygen is being delivered, then do not squeeze the bag. If there is no oxygen delivery, then squeeze the bag gently.

- A supraglottic airway is preferred to a face mask, as it is thought to reduce the risk of aerosols. (Brewster et al).

- If possible, positive pressure ventilation should only be delivered once an endotracheal tube has been inserted in the trachea, the cuff has been inflated, a viral HME filter connected, and correct placement confirmed.

- Suctioning through an endotracheal tube should occur through a closed (inline) system, in the highest level of isolation available, and by a healthcare worker in airborne PPE.

Circulation

- Rapid rhythm assessment and defibrillation should be prioritised.

- Until endotracheal intubation has occurred, compression-only CPR is recommended.

- If positive pressure ventilation is required, then compressions should be paused to allow ventilation while using a mask or supraglottic airway.

- Mechanical CPR devices should be used when available in order to reduce healthcare worker exposure to COVID-19.

Monitoring of Resuscitation

- Waveform capnography should be used to monitor resuscitation.

- Focused cardiac ultrasound may be useful to guide resuscitation efforts, and / or demonstrate absence of cardiac activity and early cessation of resuscitation.

Termination of Resuscitation

- If cardiac arrest occurs in a patient with COVID-19, a rapid assessment of potentially reversible causes should be sought.

- If no readily reversible causes are identified, then early consideration should be given to stopping resuscitation.

Advanced Resuscitation Techniques

- Advanced resuscitation techniques such as extracorporeal life support should be carefully considered and only used in exceptional circumstances for currently accepted indications (e.g. massive pulmonary embolism, or specific toxicologic emergencies).

- In the setting of a cardiac arrest in the ED from presumed COVID-19, escalation to extracorporeal life support is likely to be inappropriate.

Care for Family Members

- Family is restricted from entering resuscitation rooms, except in exceptional circumstances (for example paediatric cardiac arrest), as determined by local policies.

- Social work support is provided to family members in a safe location or via telehealth where COVID-19 precludes visitation.

- Bereavement procedures follow local guidelines for COVID-19.

Post-Resuscitation

- If return of spontaneous circulation is achieved prior to intubation, then time should be taken to clarify goals of care before intubating the patient.

-

Post-resuscitation care

We recommend:

- At the end of resuscitation attempts, everyone should remove PPE carefully, and perform hand hygiene in line with local recommendations.

- Equipment should be cleaned / disinfected / disposed of according to hospital protocols.

- Following resuscitation, it is important to conduct a debrief with team members, to specifically address:

- Clinical care and decision-making.

- Communication.

- PPE and prevention of COVID-19 transmission.

- Documenting/reporting any breaches of PPE policy and arranging follow-up as per hospital protocols.

- If resuscitation is unsuccessful, appropriate PPE should be used by staff when preparing the body for the mortuary.

-

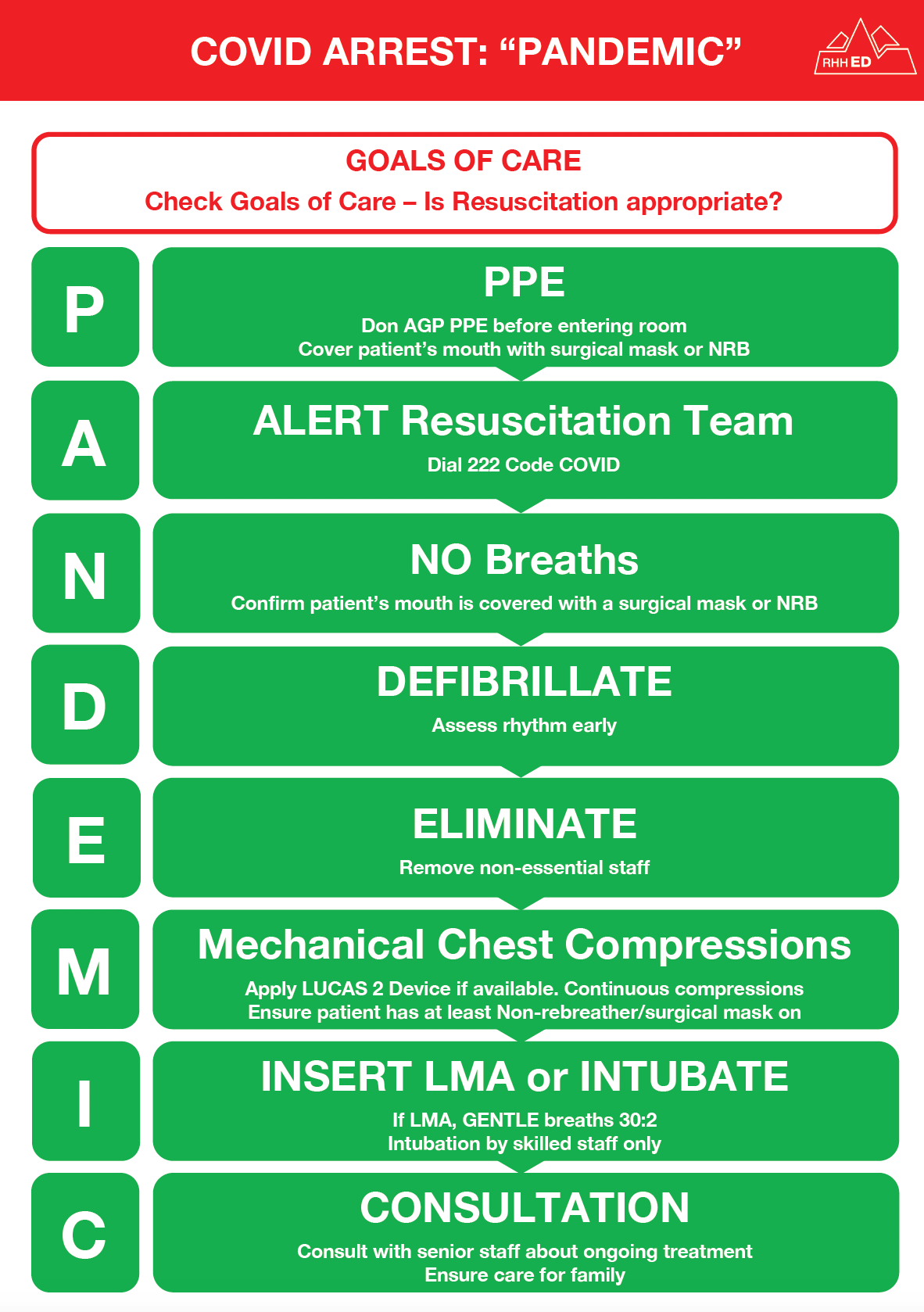

Example algorithm

An example algorithm (Royal Hobart Hospital) is provided in Figure 11 below:

Figure 11. Example algorithm from the Royal Hobart Hospital.

-

References

The following resources were used in the preparation of this section:

- Australian Resuscitation Council. ARC Statements on COVID-19. Online resource. [Link]

- New Zealand Resuscitation Council. Statements on COVID-19. Online resource. [Link]

- Resuscitation Council UK. Statements and resources on COVID-19 (Coronavirus), CPR and Resuscitation. Online resource [Link]

- Chan-Yeung M. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and healthcare workers. Int. J Occup. Environ. Health. 2004 Oct-Dec; 10(4): 421-7. [Link]

- Brewster DJ, Chrimes NC, et al. Consensus statement: Safe Airway Society principles of airway management and tracheal intubation specific to the COVID-19 adult patient group. MJA. Published online: 16 March 2020. [Link]

- American Heart Association. Coronavirus (COVID-19) resources for CPR training & resuscitation. Online resource. [Link]

- Tran K, Cimon K, Severn M, Pessoa-Silva CL, Conly J. Aerosol generating procedures and risk of transmission of acute respiratory infections to healthcare workers: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035797. Epub 2012 Apr 26. [Link]

- International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR). Consensus on Science with Treatment Recommendations (CoSTR): COVID-19 infection risk to rescuers from patients in cardiac arrest. Online resource. [Link]

- Fritz Z and Perkins GD. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation after hospital admission with COVID-19. BMJ. 2020 369:m1387. [Link]

- Public Health England. PHE statement regarding NERVTAG review and consensus on cardiopulmonary resuscitation as an aerosol generating procedure (AGP). Online. [Link]

- Department of Health. Guidance on the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) for health care workers in the context of COVID-19. Australian Government, Department of Health. [Link]

- Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Information for paramedics and ambulance first responders. Australian Government Department of Health. Online. [Link]

-

Section disclaimer

This section has been developed to assist clinicians with decisions about appropriate healthcare in Emergency Departments in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand during the COVID-19 outbreak. It is a framework for planning and responding to this pandemic, including the assessment and management of patients.

This section is targeted at clinicians only. Patients, parents or other community members using it should do so in conjunction with a health professional and should not rely on the information in the guideline as professional medical advice.

The section has been developed by an expert team of practising emergency physicians, by consensus and based on the best evidence available. The recommendations contained do not indicate an exclusive course of action or standard of care. They do not replace the need for application of clinical judgment to each individual presentation, nor variations based on locality and facility type.

The section is a general document, to be considered having regard to the general circumstances to which it applies at the time of its endorsement.

It is the responsibility of the user to have express regard to the particular circumstances of each case, and the application of the section in each case.

The authors have made considerable efforts to ensure the information upon which it is based is accurate and up to date. However, the situation is rapidly evolving, and a certain amount of pragmatism needs to be employed in maintaining such a ‘living document’. Users of this section are strongly recommended where possible to confirm that the information contained within the document is correct by way of independent sources. The authors accept no responsibility for any inaccuracies, information perceived as misleading, or the success or failure of any treatment regimen detailed. The inclusion of links to external websites does not constitute an endorsement of those websites nor the information or services offered.

The section has been prepared having regard to the information available at the time of preparation and the user should therefore have regard to any information, research or other material which may have been published or become available subsequently.

Whilst we have endeavoured to ensure that professional documents are as current as possible at the time of their creation, we take no responsibility for matters arising from changed circumstances or information or material which may have become available subsequently.

-

Resources

Resources that are relevant to this section can be accessed through the Clinical Guidelines web-based material [Link]. COVID-19 related ACEM Resources [Link], COVID-19 related external resources [Link], and the latest Government advice on COVID-19 [Link] are also available.