Always ready for the resuscitation. That’s what carrying the code blue pager is, and this night, it was a paediatric one. As I entered the special care nursery, an uneasy feeling, that of dread perhaps, filled me.

I glanced around the room, feeling the tension. On my left was a crying mother and an exhausted father, down on his knees. On my right was Jacob, one day old Jacob, struggling to breathe, profound respiratory distress. Each of tiny Jacob’s breaths were agonising; his lips were turning blue, his oxygen levels were low, dangerously so.

This night it was Paul the paediatrician and I, teamed up to care for this little soul. The resuscitation process started immediately. Between us, the mechanics of airway, breathing and circulation unravelled. Our priority was to help his breathing and secure his airway. This was not Grey's Anatomy where Jacob would cough splutter and recover after brief chest compressions and a sniff of supplemental oxygen. The reality was that he had large bilateral pneumothoraces, air was trapped between the linings of this chest, causing his lungs to collapse – invariably fatal if not addressed immediately. A team of doctors and nurses deployed themselves in the most efficient and error-free manner for Jacob to have a chance at life that had merely begun a few hours ago.

I palpated his little ribs, and inserted chest drains for Jacob, decompressing the trapped air. His breathing improved. Colour was returning to his lips. Next task to address was ‘C’ for circulation. Jacob needed intravenous fluids and steroids but this pale floppy newborn had no visible veins. I drilled a needle into his tiny leg bone, the only way to access his vasculature. He just lay there, unresponsive, not noticing the assault on his body. There is nothing scarier than a sick child.

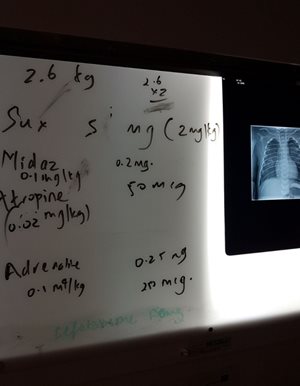

The ritual of resuscitation, worthy of the highest respect and diligence, was gaining momentum. The intraosseous access and chest drains were established. It was time to readdress the airway by means of intubation, a “breathing tube”. The emergency intubation drugs were being drawn up – fentanyl for pain, midazolam to sedate, suxamethonium to keep his body still, atropine to prevent his heart stopping, adrenaline in case it did… After re-evaluation of Jacob’s situation, we rehearsed the plan, with contingency plans for the ‘what if’s’. What if… we can’t get the tube? What if… he loses his pulse? What if…? What if …? Before we proceeded, Jacob's parents stepped in to hold their child's tiny hands. This must have been the hardest moment of their lives.

I am continually amazed at how a team of relative strangers synthetize and function to save a life. It goes without saying that no one there was ready to give up on this young life. The resolve of the team, that barely knew one another an hour before, but now intimately rely on each other, communicate clearly and boldly, to carry out the actions to save a life is awe inspiring. We got Jacob off to sleep, intubated him and took control of his breathing. His oxygen levels picked up. His vital signs normalised. The immediate danger had passed. Within an hour, he was on his way to Queensland's tertiary children's hospital with our retrieval team. He would need intensive care support for some time.

Jacob was a few hours old when I met him. I was only with him and his parents for a little while, but our connection is real. The next few days I was off work, recharging and reflecting. My mind was with him as he fought for life in intensive care. Jacob will never remember me. I held his hands. I listened to his chest. I gently examined his abdomen. I tried to make eye contact. I wanted him to know that I was there for him, to know that he was being cared for.

I’ve worked a few years in the emergency department now. I have come to realise how precious and how resilient children are. Their little bodies handle stress in astonishing ways. They believe in magic and play with imagination. They also get sick, and sick children can deteriorate so quickly, highlighting how vulnerable they are.

My part in caring for Jacob was only small in the overall mechanics of our health system. We have a group of doctors, nurses, retrieval teams, ever ready, to help the likes of Jacob and his parents get through that night. These are amazing people who leave their families to come and care for others. I am grateful to them, pleased to be part of them. To care is to have peace, to give kindness and hope. One day, we may all benefit from it.

Jacob is now doing well. He was extubated and is home with his family. He shows no signs of brain injury and can look forward to meeting his milestones in a loving setting. I wonder about all those children who do not get this chance: due to poverty, due to war, due to lack of access to medicines and doctors and nurses. I have hope. My hope is that every Jacob we save, will go on to save lives of other children who get to live in a wold better than ours.

Author: Dr Akmez Latona is an Emergency Registrar who is currently learning to be an airway wizard in the world of anaesthetics

Picture below: A white board used to minimise errors of paediatric drug calculation and administration in Jacob’s critical situation.

Do you have a story to tell? Email: [email protected]